- Home

- Jason Heller

Taft 2012

Taft 2012 Read online

TAFT 2012

Copyright © 2012 by Jason Heller

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without written permission from the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Number: 2011933458

eISBN: 978-1-59474-556-0

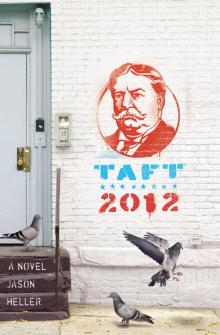

Cover design and illustration by Doogie Horner

Cover photo by Sherwood Forlee

Interior design by Katie Hatz

Production management by John J. McGurk

Quirk Books

215 Church Street

Philadelphia, PA 19106

quirkbooks.com

v3.1

To the real Irene: Margaret Smith, my grandmother, who came into this world the same week Taft was voted out of office. I hope you’re somewhere fixing a nice plate of chicken-and-dumplings for Big Bill right now.

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Prologue

Part I: 2011

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Part II: 2012

Chapter Twenty-one

Chapter Twenty-two

Chapter Twenty-three

Chapter Twenty-four

Chapter Twenty-five

Chapter Twenty-six

Chapter Twenty-seven

Chapter Twenty-eight

Chapter Twenty-nine

Epilogue: 2021

Chapter Thirty

Acknowledgments

About the Author

“The Bigness of the job demands a man of Taft’s type. He is thoroughly prepared for the task.… Never has there been a candidate for the Presidency so admirably trained in varied administrative service. Creed and color make no difference to him; he seeks to do substantial justice to all. There isn’t a mean streak in the man’s make-up. No man, too, fights harder when he thinks it necessary—but he hates to fight unless it is necessary.”

—President Theodore Roosevelt, explaining why he endorsed William Howard Taft to follow him in office, 1908

“To be a successful latter-day politician, it seems one must be a hypocrite.… That sort of thing is not for me. I detest hypocrisy, cant, and subterfuge. If I have got to think every time I say a thing, what effect it is going to have on the public mind—if I have got to refrain from doing justice to a fair and honest man because what I may say may have an injurious effect upon my own fortune—I had rather not be president.”

—President William Howard Taft, two years into his term, 1910

December 6, 1912

Dear President Taft.

I am sorry you lost your election. My daddy says Wilson is a lousy so & so. When you are not busy being President any more you can come visit me at my house because I am from Cincinnati too. I would like a Teddy Roosevelt bear for Christmas. Thank you for reading my letter. Liberty & justice for all.

Signed, Irene O’Malley, age 6

The Washington Herald

Editorial column

March 5, 1913

The Herald editorial board would like to add a final note to our exclusive reportage of President Wilson’s inauguration.

This newspaper has certainly had its disagreements with William Howard Taft during the four years he resided at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue, and we have not hesitated to point out the many occasions upon which “Big Bill” failed to live up to his predecessor Mr. Roosevelt’s fine example: for instance, his shameful treatment of that American institution, U.S. Steel. His refusal to sign legislation that would have sensibly restricted immigration to the literate. His un-American love for taxing businesses at the exorbitant rate of an entire percent of their annual income. This editorial board could go on at length!

But, for all these faults, we must acknowledge that Mr. Taft usually managed to approximate the personal behavior of a civil gentleman while president, a fact that leaves us all the more scandalized by his behavior yesterday. After saying his good-byes at the White House door in the morning, Big Bill subsequently did not bother to show up at all for resident Wilson’s swearing-in. A more egregious snub, a more unpresidential breach of propriety, can hardly be imagined!

Thus, having been granted no opportunity for a final interview with the twenty-seventh president of the United States—and, we might point out, the tenth president to be denied a second term by an unhappy American people—the Herald editorial board must deliver our parting words here upon this page: Shame on you, Mr. Taft. We surely don’t know what errand you could possibly have found so much more important than handing the reins of American democracy to your successor. Did you imagine Ohio could not wait another twenty-four hours to have its “biggest success” back? Or could you simply not bear to face a crowd of 250,000 people most eager to cheer your victor?

In any case, we have no doubt that the American people will see Big Bill again soon. After all, how could we fail to see him? The man is so large, he had to be pried loose from the White House bathtub. A proud legacy indeed, sir.

ONE

Dark.

It had been dark for so long. Dark and warm and wet and heavy. And silent.

So silent.

But not entirely so. He could hear things sometimes. A low hum of machines. A distant peal of laughter. A soft patter of either rain or tears.

He could feel things, too. The settling of the soil. The tickle of roots. The stately migration of the seasons.

And hunger. Good lord, the hunger.

He gnawed at the loam sometimes as he dreamed. He imagined he was buried under an avalanche of roasted chicken and brown gravy and custard. All he need do was eat his way out.

Instead, he slept.

That is, until the lights came.

It was a twinkling at first. They flashed intermittently, these lights, and then they quickly disappeared. He felt the dull thud of concussion, too, but knew not from where. But each flash and each thud brought him, bit by bit, out of his slumber.

Damnation, was he hungry.

With the hunger came memories. They lasted only as long as the flashes of light. First was a vision of a woman. A thin, pale woman. She spoke with difficulty, but she was happy, and she was strong-willed and alive. Even from this distance of space and time and consciousness, he drew from that strength.

Then there were children. Small ones and grown ones. There was a house, white as though carved from ivory. There was a man: bespectacled face round and beaming, voice so much louder than his own.

Then there was a smell. O glorious smell! The memory of it alone was almost enough to quell his ravenous, belly-clawing hunger. It was cherry. Cherry blossoms. The specter of the cool, sweet scent crept across his soul like a song. It came and went, but each time it faded, he clutched at it as if it were his own life’s blood.

Then, one day or minute or millennium later, he didn’t simply dream of the cherry blossoms. He smelled them.

The scent washed over him as he bolted upright. Other smells filled his nostrils too: rain and smoke and the familiar tang of roses. The cherry was faint, but it was there.

He had to find it. He ignored his hunger, ignored his pain, and pulled himself out of the infernal pit in which he’d found him

self. He knew he was slathered in mud. No matter; he’d had mud slung at him before.

Groaning, his voice horribly coarse, he staggered into the light rain, looking for his beloved cherry blossoms. But there were none. It was autumn. The blossoms were long gone.

So instead he ran toward the sanctuary. The place where his one true friend slept.

The fountain.

But before he could make it there, he heard screams. He answered them in kind. He kept running.

That’s when he heard a crack like thunder and felt a fire like lightning in his leg.

He fell. His waking dream had passed.

When he woke again, water was running down his face. He could feel it stripping the mud from his skin and dripping from his mustache. He looked up. Hovering over him were men and women with brightly lit machines perched on their shoulders.

In the distance, a man ran toward them. He held what looked like a gun. He opened his mouth. Words came out.

“Hey, turn off those cameras! Back away! Oh, my God—that face. That’s impossible. Holy shit.”

CLASSIFIED

Secret Service Incidence Report

WHG20111107.027

Agent Ira Kowalczyk

At approximately 1042, an oversized mammalian figure covered in mud appeared behind the White House South Lawn Fountain, approaching the press conference in progress on the lawn. It was unclear to me for several seconds whether the intruder was a man or a large animal as it lurched toward the crowd while moaning loudly. As the closest perimeter guard, I drew my firearm and ordered the intruder to halt while the executive guard secured POTUS. The intruder bellowed louder and attempted to proceed past the South Lawn Fountain in the direction of POTUS and the press corps. I discharged my weapon once, striking the intruder in the leg, and he collapsed against the fountain. I approached and saw that the water from the fountain, along with the morning drizzle, was washing the mud from the intruder’s body. He was a very large man, over 6 feet tall, probably 300 pounds, wearing a formal tweed suit. He had white hair and a handlebar mustache. My first thought was that he looked like some sort of deranged presidential history buff dressed up as William Howard Taft.

From Taft: A Tremendous Man, by Susan Weschler:

I’ll never forget the moment I first saw him on the television screen. Not a picture—him. There was no mistaking him. I’d been studying the history of the man who owned that plump, jowled, puffy-eyed face my entire professional life:

Taft.

William Howard Taft. Twenty-seventh president of the United States. Weighed in at 335 pounds. Worked with unceasing devotion to the job for four years—but was so honest a politician, he ended up infuriating every single interest group that had ever supported him. Lost his 1912 reelection bid in a miserable, crushing defeat. And then just disappeared the morning of March 5, 1913, the day his successor, Woodrow Wilson, was inaugurated. Taft was never seen or heard from again; his last known words, spoken right outside the White House just hours before Wilson took the oath of office, were: “I’ll be glad to be going. This is the loneliest place in the world.” After that sad utterance, Taft never showed up for the ceremony. Or anything else. Ever.

Which meant the chaotic footage they kept replaying on CNN couldn’t be real. Couldn’t be him. How could he be here now, a century later, stumbling mud-covered into the midst of an unsuspecting White House press conference?

And yet that was clearly no fake girth, no Halloween mask. It was either the oddest terrorist attack in history, the stupidest reality-show prank imaginable … or it was Taft.

Like some sort of jolly were-walrus, he sat on the edge of the South Lawn Fountain, blinking and grinning. He was still filthy, but the rain had finally uncovered most of the man. He wore a great wool overcoat, a suit so stuffed that it strained at the buttons, and a huge filthy mustache that swirled and twirled and bristled across his upper lip. Beneath his feet, the water of the fountain had turned faintly red. He appeared to be in shock—and then he spoke. His voice was much higher and more melodious than you’d expect from such a giant of a man as he uttered the words that now live forever in the annals of history: “I will gladly grant a Cabinet position, of your choice, to the first upright citizen who brings me pudding cake and a nice lobster thermidor.” Then, of course, he collapsed.

TWO

He had slept, and woke, and slept again. Doctors had come and gone. So had men in black suits. Both had asked a great many questions. One or the other had drawn blood from the crook of his elbow and even had the unmitigated gall to clip a bit of hair from his mustache. The hair had been quickly sealed in a small transparent bag, but he felt scarcely strong enough even to wonder what that was all about, much less ask. Through it all, peculiar electrical devices whirred and pinged, and he faded in and out of consciousness.

Finally, after his third or fourth doze, he sat up, lucid, hungry. Alone. He was in a well-appointed bedroom suite; under the bed sheets, he was naked and clean. Draped over an armchair lay a fresh gray suit that looked to be close to his size, though for some reason it included neither waistcoat nor hat. He climbed out of bed and found that the suit was impeccably tailored, but it was still difficult to squeeze into, particularly his left leg, the upper half of which was swathed in an ungainly bandage.

Taft didn’t recognize the room, but he knew the smell of the place. It had filled his nostrils much as it had saturated his soul over the past four years.

He was in the White House.

No sooner had he spit-shined his shoes and curled the ends of what remained of his mustache, a knock came at the door.

“Yes, by all means, come in!”

The door creaked open, and a tall, thin man in a suit—also missing its waistcoat!—walked in. He crossed the room, smiled, and offered Taft his hand.

“Mr. Taft, please. Don’t try to get up. You’ve been through a lot in the last twenty-four hours.”

“It appears I have! And who might you be? Are you here to bring me my meal? You will be my eternal hero if you could run down to the kitchen and fetch me a ham or two.”

The man closed his eyes for a brief moment before smiling again. “Dinner will be coming soon. First, I need you to listen. It may not seem like you were sleeping for long, and Lord knows we have no idea how or why this happened. But you went missing from the White House … quite some time ago. This is not exactly the world you remember.”

Taft laughed. “Not the world I remember? Why, I’d have to agree with you there. Today I’ve been shot, assaulted with strange machines, and spoken to in riddles. I appear to be in a world where the president of the United States can be condescended to like a child. By a manservant such as yourself, no less.”

“Mr. Taft,” the man said, “I need you to keep an open mind here, today and in the coming days. There is a lot you’re going to need to adjust to. First of all, I am the president of the United States. Not you. Not Woodrow Wilson. Me.”

Before Taft could counter him, the man raised his hand and pressed on.

“You’ve been missing and presumed dead—one of America’s great mysteries—for a very long time. Don’t worry, the United States is still strong, still proud, still prosperous. But—” He hesitated. “Well, I’d better just say it. You’ve apparently been asleep for almost ninety-nine years. Today is November 8. The year is 2011. Mr. Taft, welcome to the twenty-first century.”

Transcript, Raw Talk with Pauline Craig, broadcast Nov. 9, 2011

PAULINE CRAIG: A giant beast of a man bursts into a presidential press conference, is shot by Secret Service, and now, two days later, the White House is telling us that this befuddled intruder in a carnival mustache really is the missing former president William Howard Taft. Almost a hundred years after he vanished. I’m used to the government telling whoppers, but come on, now! Well, one way or another, it’s history in the making, folks. You’re living it. And Raw Talk is here to break it all down for you. Our first guest today, with us via satellite, is Director of Na

tional Intelligence James Mackler. Director Mackler, you’ve come on Raw Talk, much to our amazement, to back up the president’s outrageous claim earlier today that the man who stumbled onto the White House lawn has turned out to be the real William Howard Taft.

JAMES MACKLER: Thank you, Pauline. Under normal circumstances, an ongoing national security investigation wouldn’t be something we’d publicly comment on so quickly. But with Monday’s bizarre incident happening live in front of cameras, and—and with the startling facts we’ve uncovered, the president wants to get the information out to the public as quickly as possible, to minimize confusion and head off any worries about possible terrorist threats. So, here it is. Let me first explain—there are many levels of government security. There’s secret, and then there’s top secret—

PAULINE CRAIG: And then there’s SCI, sensitive compartmented information, which is the very highest top secret.

JAMES MACKLER: Yes. We compartmentalize the most extreme federal security information. And in the very smallest compartment—the information that, until now, no one outside the tightest, most secure handful of officials has even needed to know even existed, much less known what it is—is the identification code every president since the Civil War has memorized to protect the government against infiltration by a presidential impostor.

PAULINE CRAIG: In case something like—well, something like this happens.

JAMES MACKLER: Yes. It’s never happened before. No president’s identity has ever been called into question, until two days ago. We asked our apparent Taft for the presidential ID code. He knew it.

PAULINE CRAIG: He knew it. I see. And you’re more prepared to accept the idea of a total violation of the laws of nature than the idea that a government secret could have leaked.

JAMES MACKLER: There are secrets, and then there are secrets, and then, beyond those, there are the secrets so secret they keep secrets from each other. I don’t know how to explain his appearance after a hundred years, but I do know as an absolute certainty that that man could not know that code unless he used to sit in the Oval Office.

Taft 2012

Taft 2012